I Was A Child: The Childhood of the World

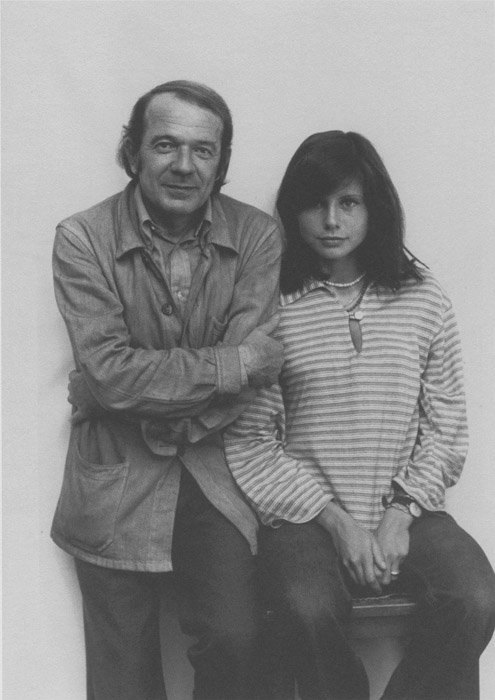

As with so many things, we turn to Gilles Deleuze for inspiration. In his wonderful interviews with Claire Parnet, Deleuze is prompted to comment on his childhood and what it means to write.

He responds, "Writing is becoming, becoming-animal, becoming-child, and one writes for life, to become something, whatever one wants except becoming a writer and except an archive."

What exactly does this mean?

As soon as one becomes a writer, so the theory goes, one ceases to become something new. In essence, one becomes irrelevant, with nothing original or important to say. Not only does the individual lose the ability to transform themselves, their writing also suffers from the loss of the power of transformation. One no longer understands, for example, what it means, and what it takes, to write in the first place. The wellspring of joy and affirmation, from which writing often bursts forth, runs dry.

When one identifies themselves as a writer, says Deleuze, they have the tendency to become sedentary and complacent in their modes and habits of thinking and describing the world. They lose their nomadic perspective, so to speak. But, at the same time, they retain or gain their identity, i.e.: "I am a writer." In opposition, Deleuze presents another type of author, a "writer" that avoids the archive, losing themselves in their work. Another orientation to writing takes place, then, because the writer has engaged with the act of having something to say, to "becoming-animal" or "becoming-child".

Deleuze goes on to explain, in reference to childhood, that there are two types of "places" from which individuals write. The first, it could be said, is from the perspective of a "memorialist", which is to say, an individual who writes from the experience of one's own childhood. To be sure, we all have examples. Of course, this type of writing appeals directly to the private life of memories, accessing the personal archive of an individual's childhood. This model of writing, this personal archive of life, has zero interest for Deleuze. Why? Well, it just doesn't tell us enough about the world, or ourselves. It's a collection of identities.

In contrast to the "memorialist", Deleuze proposes a second type of author, one who writes from what he terms, the "childhood of the world". What a spectacular concept, one worth repeating, hearing it roll of your tongue: "The childhood of the world". The phrase contains just the right amount of staccato and optimism. It's as cautious as it is upbeat. That being so, and all things considered, Deleuze is absolutely convinced that writing has nothing to do with memory. It's something else entirely.

Following Ossip Mandelstam, Deleuze remarks that writing, therefore, is "pushing language to the limit, stuttering, becoming an animal, becoming a child". It has nothing to do with digging "through family archives", but rather, inventing a way to express a new language, within a language. Children are so great at this: inventing their own language as they go along.

What lessons can we learn from this line of thinking? How can it be incorporated and applied to our individual, practical lives? Can the concept of the "child of the world" be utilized to help us as we write and as we continue to create and draw the contours of our lives?

Well, in a certain, dare we say "autobiographical sense", we strongly believe that everything we have learned, we have learned from children. Not from our memories of childhood, but from their expressions towards the world. It's not that childhood isn't interesting on a personal level, remarks Deleuze, because it most certainly is, but rather, what is of most interest is the "emotion of a child", "the sense of being a child, any child whatsoever." It's a principle that we hold dear: as we write, as we design, and as we architect experiences for children. We all know children are amazing, but they're even more amazing than we give them credit for.

As Deleuze writes in What Children Say, "Children never stop talking about what they are doing or trying to do: exploring milieus, by means of dynamic trajectories, and drawing up maps of them". They're always exploring the world around them, trying to figure things out as they go along. Everything is new and exciting, and they want to taste it, and feel it, and see it - always for the very first time. Nothing is more new than the ordinary and everyday. If only we could learn to see the world with their mouths, fingers and eyes. If only we had the same confidence in our mistakes.

Yet, and with everything in mind, Deleuze insists, "'I was a child,' and the importance of this indefinite article is the multiplicity of a child. The indefinite article has an extreme richness." Lest we forget, we must never lose the perspective of the "childhood of the world". We must write to become a child. Or, if you prefer, become an animal!