Nothing Can Replace Painting

David Hockney - Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures).

I've been reading a fair amount of interviews with David Hockney. I find them so ripe and resplendent with observations and insights. They're almost like viewing one of his landscapes. As soon as you discover one layer, a color or posture leads you to another previously unexplored depth. There's so much wonder and vastness in his work. It's as if you'll never be able to finish looking, let alone finish the conversation.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, David Hockney has sufficiently devastating remarks to make on the nature of photography. His comments are aimed directly at the totality of vision that photography lays purchase to: primarily that photography is omniscient. As he states, "Photography likes to claim that it is just putting reality in front of us. But that's obviously not the case." What Hockney goes on to lament, but only just so, is that from the start, the authenticity of photography has been called into question.

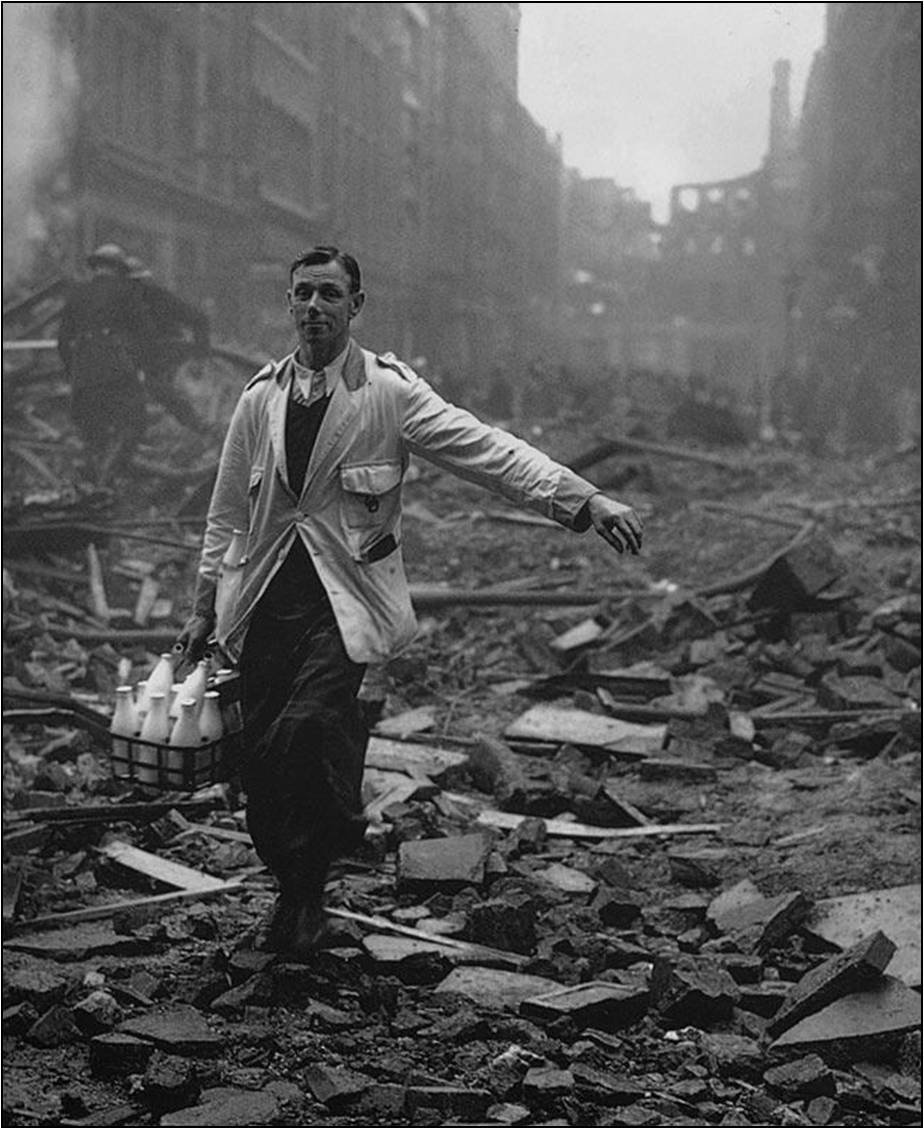

As Hockney explains, "There's a famous shot of bombed-out London the morning after a raid. There's a milkman walking over the ruins. It was made in 1941 to tell people to keep calm and carry on. But he wasn't a milkman: he was the photographer's assistant, he'd just put on a coat. You could say it was faked, but at the time it was doing a job of work: it was saying 'Carry on'. If it were a painting, you wouldn't worry about whether it was a real milkman who was the model."

The point, then, is not that photography is a performance. Of course that is an acceptable style, or mode of presentation. Instead, the point is that photography tends to lend the impression that it has a special claim to reality. That photography, as a matter of fact, represents, or is able to capture, the truth.

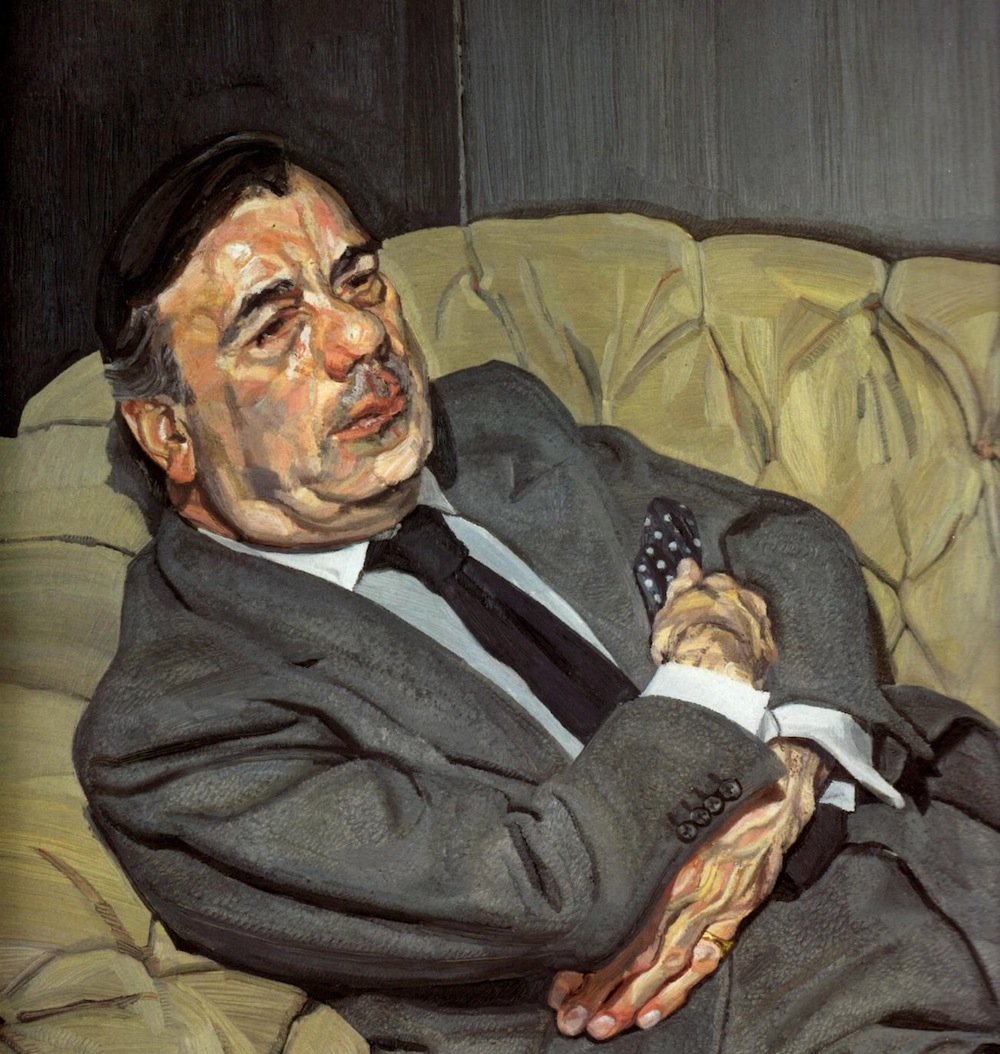

Needless to say, nothing could be further from the paintings of David Hockney. This is precisely why Hockney claims that the portraits of Lucian Freud are, in his own words, "as good of portraits as done by anybody." They manage to portray reality, in a way that photography cannot: with a stunning sense and degree of acuity. In this respect, then, people are as much landscapes for Freud, as Woldgate is a portrait for David Hockney: they are virtually, infinitely explorable.

Hockney, to be sure, spent time working with photography, while Freud focused solely on painting, which leads him to express: "We are moving out of what we thought photography was and back to painting." Photography, therefore, increasingly loses its claim to the type of vision and veracity that painting constantly endures and provides. Still, Hockney suggests, "people believe that photography catches reality. It's catching a bit of it, but not that much of it."

Imagine, for instance, standing before a magnificently arresting sunset. You're instantly paralyzed. Your eyes struggle to find a place to rest, as they traverse across the sky. Within seconds, you're enfolded in a matrix of unexpectedly vivid and penetrating colors. Helplessly, you anxiously attempt to further immerse yourself in the abundance of this ephemeral moment. It's just so beautiful. You want it to last forever. You want to bathe in the vast swathes of light. Yet, and despite your best efforts, you begin to feel the radiance of the sun as it starts to position itself to set. Its strength, while constant, is somehow fleeting. "One more moment", you plead. You snap a photo in the hopes of later reliving this moment, but the photo will only later betray your vision.

Interestingly enough, Henri Cartier-Bresson, unarguably one of the greatest photographers of the mid-twentieth century, gave up photography in the last few decades of his life, and turned to drawing. David Hockney makes a wonderful observation on this decision: "He was the master of that period: a fantastic eye. He began when Leica was invented, and he gave it up a little before Photoshop was invented. His roles - don't crop the picture, for example - would be incomprehensible to a young twenty-first-century photographer. You couldn't have a Cartier-Bresson again, because you would never believe it. Today it would be artificial."

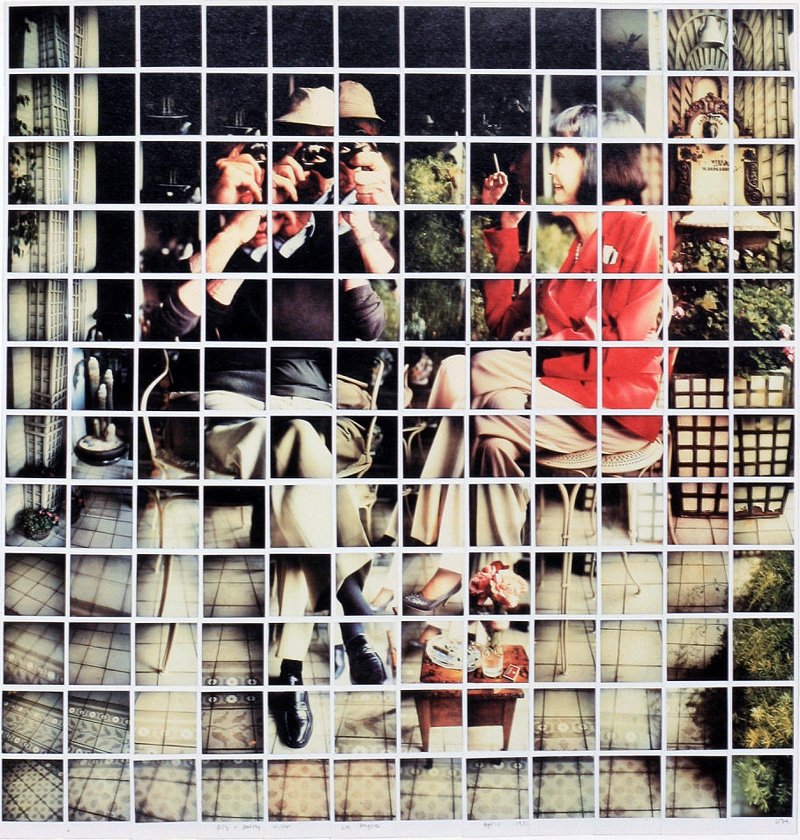

When you view a Hockney photo collage, you can feel him trying to slowly, almost methodically, put the pieces together. He's trying to work out, at least on stage, what exactly photography means for the history of art. Polaroid by polaroid, you can feel him strenuously attempting to overcome our cultural attraction to, and misperceptions of, photography. "Most people feel that the world looks like the photograph," explains Hockney. "I've always assumed that the photograph is nearly right, but that little bit by which it misses makes it miss by a mile. This is what I grope at."