The Obligation to Write

There are so many wonderful books that inspire us to become better writers. To be sure, we all have our favorites.

Maybe it's a few lines in Italo Calvino's wonderful Six Memos for the Next Millennium; or the specificity and enchantment to be found in the sparingly beautiful paragraphs of Natalie Goldberg's Writing Down the Bones; or, further still, the magical, and at times, ineluctable stories to be discovered in the letters and conversations of Max Perkins.

One of the best, perhaps, is Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, by Anne Lamott. It's so light and playful. Yet, at the same time, it's also cautious and reserved, as it methodically explores the dark and serious depths of emotion, with such adroitness and humanness. Slowly, if not daftly, it builds up our confidence to trust in the momentum it takes to meet our obligations to write. Nevertheless, for all its wizardry, and guiding light, I've remained on the look out, with an almost insatiable desire, for further furloughs into the recesses of writing. Not just how we write, but why we write.

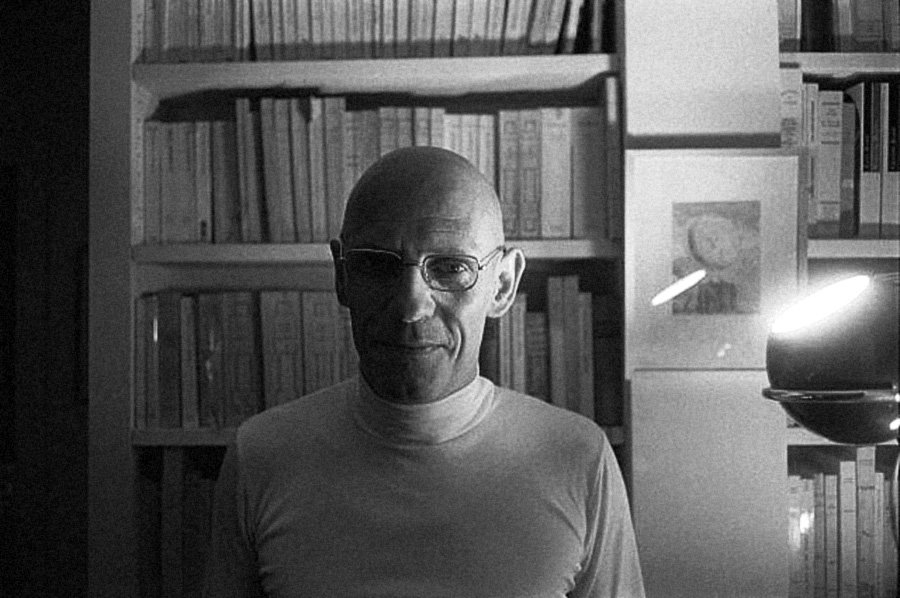

I think I found it, if but for a moment, in the interviews of Michel Foucault. In particular, in the conversations with Claude Bonnefoy, ironically translated into a text, Speech Begins After Death.

As aspiring writers, we're constantly inquiring into various methods, techniques, and styles. Why did Hemingway stand to write? Is writing in the morning, as Nietzsche confesses, the most efficacious and timely? Or, as Cioran shared, does the night, coupled with seemingly endless existential bicycle rides around a lantern-lit city, induce proficiency and thought?

In a more complex tone, we query: What is it about travel that evokes the sensation to write? Why does a journey, if it does at all, elicit a certain style or mannerism of thinking? If a line of thought is exposed, whereas it might have otherwise remained unprompted, disguised amongst our daily, habitual live - how do we solicit such encounters?

Anything to help us write more effectively, and, for most of us, more efficiently. We're eager to learn, for example, how our heroes took up this noble, and at times, inauspicious task. (I dare not say profession, at least not as an author, lest we forget Roland Barthes.) However, there also needs to be a frame of reference for "why we write", or from whence the impetus is initiated. Michel Foucault points the way.

Foucault was a great diagnostician, perhaps this is precisely where his lucid, lilted, languid prose arose - from the art and science, or the life-practice, of diagnosing, i.e.: trying to elucidate that which remains hidden. Not the desire to adorn language, but to reach the truth of that which must be said.

Here's Foucault, offering a clinical, if not philosophical, approach to drawing the contours of what a definition of writing might encompass, or rather, put into motion:

"Writing consists essentially of doing something that allows me to discover something I hadn't initially seen."

Less phenomenologically, he goes on to articulate, "When I begin to write an essay or a book, or anything, I don't really know where it's going to lead or where it'll end up or what I'm going to show. I only discover what I have to show in the actual movement of writing, as if writing specifically meant diagnosing what I had wanted to say at the very moment I begin to write." (46)

Unlike physicians, who, as Foucault explains, normally reduce language to silence, Foucault instead, attempts to identify and examine a problematic within a certain lineage of history or philosophy - through writing. In this sense, then, the pen becomes the scalpel: an instrument of exploration, no less than excision.

As Foucault states, "The physician listens, but does so to cut through the speech of the other and reach the silent truth of the body." (35) The physician speaks, therefore, only to offer a diagnosis and subsequent therapy, but language itself is restricted, bound to orders and instructions. "The surgeon discovers the lesion in the sleeping body, opens the body and sews it back up again, he operates; all this is done in silence, the absolute reduction of words." The physician, therefore, uncovers the truth of what the body speaks.

In contrast, the writer uses language to diagnose, then create or foster a type of therapeutics, personalized to the individual needs of a particular situation. Which is to say, the "activity of language", or the very act of writing itself, is precipitated, not from having "something in mind" to say, but rather, from the necessity, or obligation to write.

"When it is no longer possible to speak, we discover the secret, difficult, somewhat dangerous charm of writing." It is precisely here, on this point, that we can see Foucault's extraordinary affinity with Nietzsche, whom he describes as a great diagnostician, exerting a kind of radical, "violent therapy for the diseases of culture".

As a challenge to ourselves, or perhaps to the history of philosophy, Foucault inquires into the nature of writing, trying to examine from where the compulsion to write germinates, what it means, and in relation to what necessity it is brought on.

"One thing I feel certain of is that there's a tremendous obligation to write." As he explains,

"This obligation to write, I don't really know where it comes from. As long as we haven't started writing, it seems to be the most gratuitous, the most improbably thing, almost the most impossible, and one to which, in any case, we'll never feel bound. Then, at some point - is it the first page, the thousandth, the middle of the first book, or later? I have no idea - we realize that we're absolutely obligated to write."

There are at least two modes or states of obligation that Foucault describes. The first, is, what he calls, "a form of absolution". What this means is that through writing, the form that obligation takes reveals itself, in this instance, as the persistence to carry out the task to release yourself from the compulsion. Which is to say, to write is to absolve yourself of your duties to write. "That absolution is essential for the day's happiness. It's not the writing that's happy, it's the joy of existing that's attached to writing, which is slightly different."

The second mode of obligation, or how that obligation manifests itself, concerns the "inexhaustibility of language". There's a sense in which, as so many writers know, we're always striving to write that last sentence. "Ultimately," as Foucault states, "we always write not only to write the last book we will write, but, in some truly frenzied way - and this frenzy is present even in the most minimal gesture of writing - to write the last book in the world." Thus, in a way, we're constantly aware of the utter exhaustion that writing involves. Multiple iterations, and still, the persistence remains - just one more sentence. It'll be the last sentence.

Lastly, and most poetically, Foucault writes:

"We write to hide our face, to bury ourselves in our own writing. We write so that the life around us, alongside us, outside, far from the sheet of paper, this life that's not very funny but tiresome and filled with worry, exposed to others, is absorbed in that small rectangle of paper before our eyes and which we control. Writing is a way of trying to evacuate, through the mysterious channels of pen and ink, the substance, not just of existence, but of the body, in those minuscule marks we make on paper. To be nothing more, in terms of life, than this dead and jabbering scribbling that we've put on the white sheet o fpaper is what we dream about when we write. But we never succeed in absorbing all that teeming life in the motionless swarm of letters. Life always goes on outside the sheet of paper, continues to proliferate, keeps going, and is never pinned down to that small rectangle."

"The role of writing," says Foucault, "is essentially one of distancing and of measuring distance".